New York, New York! We are sending this from the USA, as we are in New York City. Yes, you guessed it. We are among the UNGA’s folks (United Nations General Assembly).

For most of our stay, we will participate in events and attend meetings in New York. We will also have a quick trip to the World Bank headquarters in Washington, D.C. to deliver a lightning talk.

We are carrying one core message: the future of youth productivity in West Africa is Highdigenous.

If you are around NYC in the next few days, let’s meet! If you know people we should meet, thank you in advance for your intros 😊

As a quick refresher: We are all about unlocking youth productivty at scale in West Africa by blending high-tech with indigenous and community insights.

But what does the Highdigenous approach to upskilling look like in practice?

Below, we are sharing a quick case study about the Highdigenous approach in action. We hope you will enjoy the read as much as the Kabakoo community enjoy working and learning through the project.

But before going further, here comes, of course, the song of the month: 🎶 “Châteaux de sable” by Sael and Benny Adam. Montréal pop with Sahelian vibes. Can you feel that guembri? And yes, the song’s reflection on creating beautiful but fragile things resonates deeply in the Sahel.

From handwoven fans to high-value skills: Le Nid de Bamako as a case study of Highdigenous upskilling

How do you translate a globally acclaimed upskilling approach into tangible jobs and skills? This month, we are excited to share, as our newsletter, a living case study from our Bamako hub that shows exactly how our “Highdigenous” approach builds youth productivity, creates economic value, and leaves behind a beautiful, lasting asset for the community.

“Le Nid de Bamako” (The Nest of Bamako) is what happens when centuries-old craftwomanship, contemporary design, and regenerative economics collide. Over six intense weeks, a team of 16 learners, guided by a duo of world-renowned mentors, transformed about 2,000 handwoven fans from centuries-old craftswomanship into a 130 m² experimental pavilion. Le Nid de Bamako, a shimmering, ventilated shell, is both shelter and learning place: a collective experiment in regenerative architecture, built with local economies and the Sahel’s craft intelligence at its core.

Where it started

Kabakoo’s Highdigenous philosophy—high technology with indigenous knowledges—frames the project. Season #3 of Bamako.AI on the topic “Artificial Intelligences & Radical Care” set the brief: ‘Construire son nid’, an open module inviting learners to design and build a modular nest using local materials—calabash, rattan, bamboo—and the Sahel’s weaving traditions. The outcome wouldn’t be a model in a studio but a collective, usable space on Kabakoo’s rooftop: an experimental room for the community.

Cast & roles

- Cheick Diallo, internationally recognized Malian designer; knowned for his furniture and objects challenging common perceptions of design from African contexts with their mix of centuries-old craftsmanship and contemporary sensibility. His work features in several major permanent collections, among others, MAD Museum (US), Centre National d’art et de Culture Georges Pompidou (France); Manchester Museum of Art, (UK); Brooklyn Museum (US); Vitra Design Museum (Germany), etc.

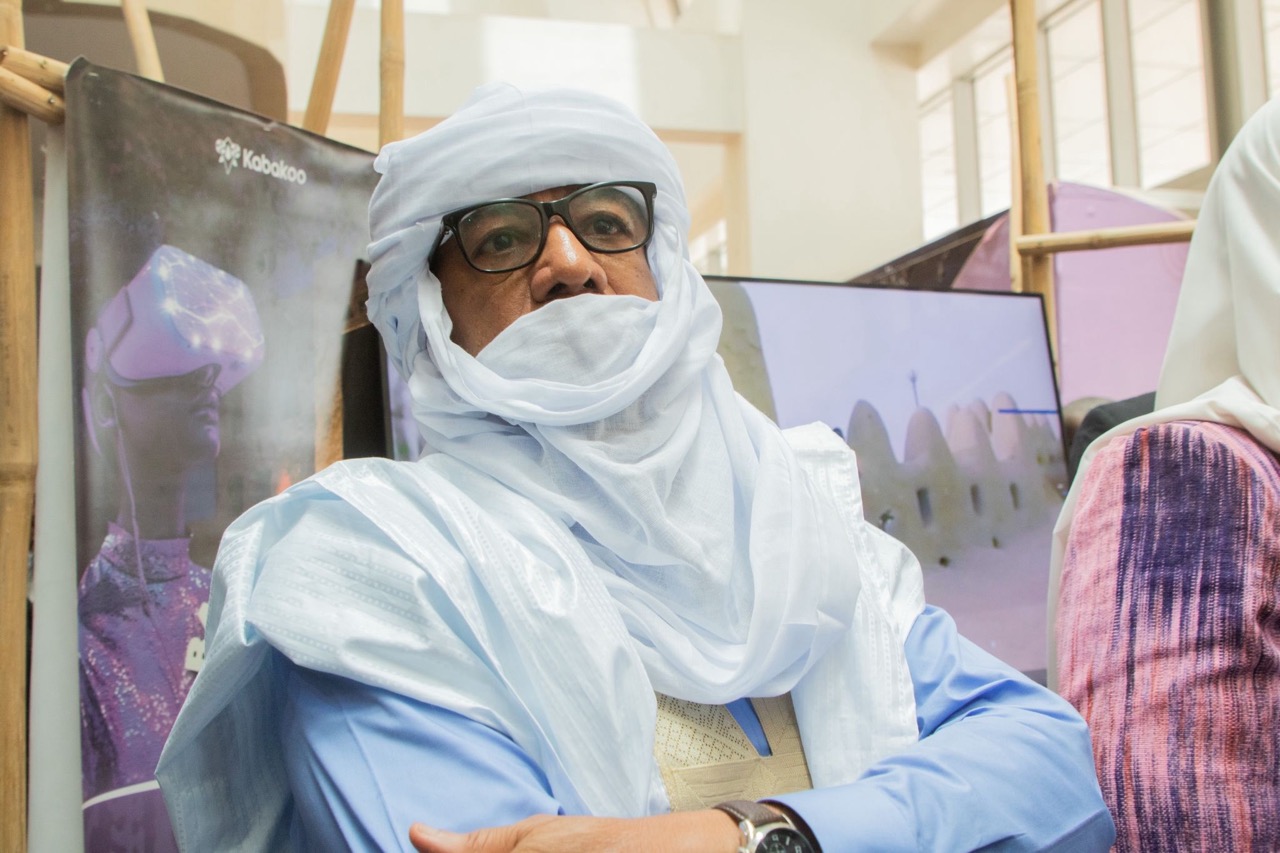

- Mamadou Koné, Malian architect renowned for his pivotal role in the reconstruction and preservation of Timbuktu’s UNESCO World Heritage,particularly following the destruction of significant cultural monuments in northern Mali in 2012. He supervised the delicate reconstruction of Timbuktu’s mausoleums that are key elements of the town’s cultural and spiritual legacy, using century-old building methods. He is also renowned for his work on restoring the unique architectural traditions of the Dogon/Bandiagara cultural landscape. Yet, his multiple works have also shaped the contemporary landscape of Bamako, grounding him firmly in the present.

- Samaou Touré, master weaver from Gao. She left her hometown of Gao for the first time in her 60+ years to join the Kabakoo residency in Bamako. She is a living library of wickerwork techniques. Thanks to her joining the Kabakoo learning community, we could ensure a deep connection to the craft's origins.

- 16 learners, organized in four groups.

- A compact team of welders, carpenters, plus neighborhood suppliers of bamboo and raffia.

“Whether you are restoring the great mosques of Timbuktu or designing a pavilion from handwoven fans, the fundamental questions are the same: How does the structure breathe? How does it respond to the sun? How does it gather people? Le Nid is a contemporary translation of these core principles. We taught the learners to listen to the materials around them, and the materials taught us how to build.” Mamadou Koné, architect & Timbuktu’s UNESCO World Heritage restorer

Design, collectively

The project unfolded over six weeks, a compressed timeline that forced rapid innovation and intense collaboration. The design phase ran like a community lab: weekly sessions with Cheick Diallo on Tuesdays/Thursdays and on Wednesdays with Mamadou Koné. The other days of the weeks were dedicated to self-directed research and peer workshops.

The 16 learners, from backgrounds as diverse as IT, photography, and logistics, were split into four teams, tasked with a monumental challenge: to collectively design and build a functional, beautiful structure.

The initial prompt was open: “Construire son nid” (to build one’s nest). The teams explored a universe of biomorphic forms: a snail’s shell, a mushroom’s cap, a beehive. The process was intentionally emergent. As Diallo later reflected, “I didn’t want to impose an idea. I wanted a debate to be established between the learners and myself... I tried to propose a universe to get out of the commonplaces we are used to seeing.”

Eventually, a consensus formed around the concept of a tortoise shell—a powerful symbol of shelter and resilience. The mandate then was not to imitate nature, but to be instructed by it. The carapace abstracts the idea of protection and scale, translated into modules that could be woven, assembled, and repaired by hand.

Remote‑first design. For three weeks of the six‑week sprint, Cheick Diallo was traveling across Europe; Mamadou Koné spent one week in Bandiagara for some of his work on the Dogon Plateau. Working with world-class mentors always on the move, Kabakoo is used to this. The team hence move to videoconferencing to keep the studio rhythm. The design sessions hence became a case study in hybrid collaboration. Zoom calls connected continents, while peer-to-peer workshops at the Kabakoo hub in Bamako translated digital ideas into physical mock-ups.

From sketch to kit.

With the concept solidified, the project crashed into the beautiful, messy reality of construction. Mamadou Koné, back on site, translated the organic vision into structural logic. He and the learners took measurements on the rooftop, translating them into CAD drawings, and determining the specifications for the load-bearing steel frame—a metallic skeleton supporting a double‑curved skin of wickerwork modules. The modules would not be woven in situ but built from everyday Sahelian fans (called “fifalan” in Bambara language), iconic, affordable, and replaceable, mounted like scaled shingles.

The atmosphere at the Kabakoo co-learning space transformed into that of a bustling atelier. Welders arrived to bend and join the steel arches, their work guided by Koné’s plans. Carpenters worked alongside learners to prepare wooden elements. But the central activity was the preparation of the 2,000 handwoven fans that would form the structure’s scales.

The materiality: from fan to façade

As main material, the team chose fifalan, the common hand-fan. It is an ubiquitous object, a piece of everyday Sahelian life, yet 100% handmade in symbiosis with nature. “From shell-scale to fan,” Diallo explains, “we told ourselves: “it can be an opportunity to show that we can use materials differently”.”

During the construction, tools were simple by design: drills, clamps, shears, and wire. Learners rotated through safety briefings, module fabrication, rigging, and quality checks. The learners, working in shifts, organized the fans into lots, attached them with wire, and mounted them onto the arched steel frame. The structure slowly came to life, its surface a pixelated mosaic of yellow, purple, and green woven fiber, creating a dappled, filtered light within.

Le Nid de Bamako – A living experiment

The final structure is a celebration of form and function. With its ‘lifted’ feel, the ovoid shape measures 11 meters long by 7 meters wide, rising to a height of over 3 meters. An 3-meter-wide opening invites visitors inside, where the arching metal ribs and the intricate ceiling of fans create a cathedral-like effect. The space is both monumental and intimate, a public gathering spot that feels like a private sanctuary.

The entire structure, together with the whole building, is powered by an adjacent array of solar panels, reinforcing its connection to the environment. Le Nid de Bamako is now a permanent feature of Kabakoo, a multi-purpose space for workshops, events, and quiet contemplation.

But the real deliverable wasn’t the nest itself, but the resilient and agentic problem-solving team that emerged. The learners didn’t just learn how to build; they learned how to learn, innovate, and create value together. In their context and with their resources. That is the core of the Highdigenous approach.

A room for a town. Le Nid de Bamako immediately hosted peer‑learning sessions, unplugged concerts, and public talks. The porous skin delivers daylight without glareand cross‑ventilation; at night simple lightning makes the wicker read like a woven sky.

Climate literacy embedded. The scaled overlap shades the deck below while allowing air flush. Every module is hand‑replaceable using local materials and skills. Nothing is glued to the substrate; the system is demountable.

Regenerative by design.

- Materials: plant‑based (raffia) plus recyclable steel;

- Maintenance model: damaged fans can be rewoven or swapped;

- Afterlife: the shell is designed to be re‑skinned seasonally or repurposed as a market canopy.

The impact: high-value skills and economic value creation

Le Nid de Bamako is a complete economic and social prototype. It proves that we can create world-class design while building a hyper-local value chain—from the 2,000 fans that supported artisan livelihoods to the 16 young people who acquired high-value skills. This is the future we are building: an ecosystem where heritage and endogenous knowledge are not just preserved, but become the very engine of our economic future.

Yes, this does look beautiful, but is a model like this scalable?

Kabakoo is not in the business of scaling the creation of pavilions. We are scaling the pedagogical engine that produces skilled, agentic, and collaborative teams. ‘Le Nid de Bamako’ is just a proof point of that engine’s output, and the engine itself is designed for scale:

- A replicable blueprint: The challenge-based mentored cohort framework is our core methodology. This project focused on regenerative architecture. Other projects have included developing a no-code app for an agribusiness, launching a digital marketing campaign for artisans, or designing a hardware solution for farmers. The context changes, but the highly effective, experiental learning process remains the same.

- A scalable tech backbone: This intensive, hands-on project was supported by our core technology. Learners access foundational modules on our mobile app, receive 24/7 support from our AI Mentor, and collaborate via integrated tools like WhatsApp. This tech-enabled core allows us to manage and support hundreds of such team projects simultaneously across different locations with minimal overhead.

- An economically viable model: This high-impact project is a feature within our broader, highly cost-effective upskilling program. With a demonstrated 6.3x ROI for Kabakoo learners, our model is built for affordable, large-scale deployment. Intensive projects like ‘Le Nid de Bamako’ are the capstone experiences that crystallize the learning. Their value is multiplied because we meticulously document them, creating a library of authentic learning videos and pedagogical guides. This transforms a one-time project into a permanent, reusable curriculum asset.

“Le Nid de Bamako” demonstrates the quality and transformative potential of the Kabakoo learning experience. Our technology, operational model, and smart content strategy are how we deliver Highdigenous upskilling at scale.

Below a quick video of the learners giving their views and impressions on the project. As you can see, a lot of emotions.

Thank you for reading to the end! 💜🧡

Michèle & Yanick

.jpg)