Guten Tag from Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin!

We are currently in Germany, meeting partners and enjoying Berlin’s (in)famous winter. Yanick is also teaching a course at the University of Paderborn, a wonderful opportunity to share the Highdigenous approach with new audiences and gather fresh perspectives. If you know anyone in Berlin we should meet, thank you in advance for the intro!

In this edition, we introduce the Highdigenous Connection Model, our new approach to building social capital and skills through super-decentralized learning pods. We share results from a simple experiment: what happens when you rename “clubs” as “grins”? (Spoiler: simple naming tweaks matter more than we expected.) We dive deep into why storytelling and aesthetic engagement are not nice-to-have but core capabilities we deliberately cultivate.

🎶 Our record for this month is Birth of the Cool by Miles Davis, the 1950s compilation that redefined what jazz could sound like. More space, unusual instrumentation, subtlety, and collective arrangement. Sometimes it takes a cool refusal of the status quo to restructure the very grammar of a genre, be it a musical genre or a field such as upskilling for livelihoods.

What are we building?

Kabakoo designs and scales evidence-based pathways for West African youth, integrating AI, community, and cultural insights to foster the mindset and skills essential for building productive livelihoods and driving systemic change in informally dominated economies.

☀️ December 2025 Highlights

The Highdigenous Connection Model: Building skills and social capital through learning pods

Over the past weeks, we have been developing our Highdigenous Connection Model, building on our existing WhatsApp-based learning platform with a stronger focus on social capital.

This new iteration, largely developed during our Lomé Sprint, introduces learning pods—small peer groups formed through algorithmic matching based on shared interests, geographical proximity, and learning goals. These pods are designed to strengthen mutual accountability, collective progress, and local support networks while remaining closely supported by our AI mentor. Personalized learning pathways remain central, now enriched with AI-delivered micro-credentials and challenges designed to sustain engagement.

The first real-world deployment begins in the coming days, starting at the neighborhood level in Missabougou, Bamako. This is an important milestone the teams in Bamako and Lomé have been working toward, and we are excited to share insights in the coming newsletters.

From “clubs” to “grins” : When naming unlocks belonging

This month, we explored what happens when co-learning spaces are framed in ways that resonate more closely with local context and everyday social practices.

In Mali, a Grin is more than a group of peers, it is almost a social institution, an informal, tea-fueled space for debate, connection, and belonging. We wondered: if we reframe our standard WhatsApp and in person learning “Clubs” as “Grins” will it change how learners show up? (The idea came from the success of our Grin-programs during the latest edition of our festival Bamako.ai).

We sent a WhatsApp message to 1,000 of our most active learners, selected from our database based on recent activity. The message introduced our clubs using the more culturally grounded framing “Grins”, with a simple call to action, allowing learners to access the list of available groups and join one.

The primary objective was pragmatic: increase attendance at in-person sessions and observe changes in animation dynamics, before and after a shift in framing. This initiative was not designed as a formal A/B test, but rather as a rapid, field-based iteration.

The response was immediate. 83% of recipients opened the message, and 64% of those, engaged by replying or clicking the call to action (representing 54% of the initial 1,000 contacts). This confirmed once again the effectiveness of WhatsApp as a high-trust, high-responsiveness channel, but more importantly, it allowed us to test a deeper question: Does culturally anchored naming influence in person participation?

Looking at participation in in-person sessions over a four-week window, the change was striking.

More than 70% of all observed participations occurred after the introduction of the “Grin” framing, compared to less than 30% before. Among learners who received the WhatsApp invitation, nearly 70% of participations happened after the naming shift, suggesting that identity and familiarity can act as activation levers when combined through simple WhatsApp coordination.

Hence, when learning spaces are framed in ways that resonate with existing social practices, they can lower psychological barriers to entry and translate digital nudges into real-world participation. This reinforces a core tenet of our Highdigenousapproach. Scaling upskilling isn’t just about lowering data costs, signing distribution deals, or optimizing algorithms. It is also about lowering psychological barriers by leveraging the symbols and social forms/institutions people already trust. By using the language of the community (the Grin), we convert a ‘training session’ into a social ritual.

Storytelling as capability: How narrative builds agency and economic value creation

Beyond the projects we develop with mentors, learners, and value creators, storytelling has consistently been one of the most effective ways we make the Highdigenous approach tangible. But more importantly: storytelling is itself a core capability we deliberately cultivate in learners.

Research in narrative psychology supports this working hypothesis. A comprehensive review in Psychological Science in the Public Interest (Walsh et al., 2023) synthesizes evidence showing that people use narratives not merely to communicate, but to construct their sense of self, organize their past experiences, and imagine possible futures. The capacity to tell one’s own story—what researchers call narrative identity—is foundational to mental health, agency, and the ability to pursue valued goals.

Below are three ways we are treating storytelling as part of the Kabakoo upskilling engine.

1. Storytelling as learning module: Building the capability to aspire

Storytelling is a core learning module at Kabakoo. In contexts where dominant narratives often focus on failure, scarcity, or limitation, the ability to tell one’s own story is essential. Learners are encouraged to shape narratives about their journeys, challenges, and progress in ways that support growth, confidence, and projection into the future.

Through this practice, learners shift how they see themselves—from being defined by constraints to recognizing their capacity to learn, create, and succeed. We have documented this transformation in our learner portfolio analysis: learners who engage deeply with storytelling tasks show higher presence of future-oriented vocabulary and aspiration-related discourse. This is amenable to positive changes in self-perception; as clearly articulated by Hadam, a Kabakoo learner who mentions that going through the Storytelling module has given her a stronger (positive) appreciation of her small business.

Another learner’s reflection, sharing a story about his desired future, captures the mechanism at work: “Visualizing myself in this project—being among fields of several hectares, asking my employees if everything is going well—gives me endless motivation and the firm conviction that I can achieve this project.” The visualization produces both motivation and capability belief. This is a clear upside of what Powell (2012) calls “the capability to aspire” in her study of vocational education and training for poverty alleviation in South Africa.

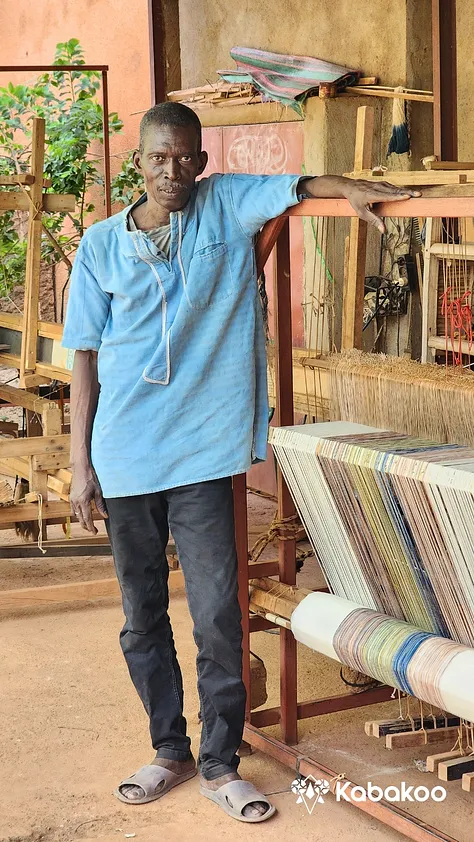

2. Craftmasters and artisans as recognized experts: Making invisible knowledge visible

One of the most consistent expressions of Kabakoo’s storytelling practice is our long-term focus on craftmasters and artisans. Across our work, masons, weavers, dyers, potters, and builders are presented as knowledge holders—not as “informal actors” associated only with the past or some sorts of mummified culture/folklore. Through portraits and interviews, they speak directly about their work, their techniques, and their journeys, and are positioned as experts in their fields. These stories are deliberately grounded in practice. By documenting gestures, materials, and processes, Kabakoo helps make local knowledge visible and transmissible.

As examples, stories such as Samaou Touré, a master weaver from Gao, who traveled to Bamako for the first time in her 60+ years to join our residency show the potential. Her story, shared as a simple written Facebook post, has gathered organically more than 765k impressions and 7.9k interactions, with no video, no effects. What resonated was the narrative itself: recognition of deep and contextual expertise and craft.

Kassim Barry’s pottery-making techniques and Ousmane Diallo’s textile weaving processes have each reached organically over 100,000 views. Abdoulaye Yampa reflecting on his journey from a failed migration attempt to metal sculptor even reached hundreds of thousands of viewers across platforms. But the view counts matter less than what happened next: learners now use these artisan techniques as foundations for their own projects, such as combining banco construction with VR visualization, bogolan patterns with digital infographics.

This is the pedagogical function of storytelling: it enables learners to recognize expertise outside institutional settings. For young audiences in particular, encountering innovation through the voices of artisans shifts perception. It feels closer, more familiar, and attainable.

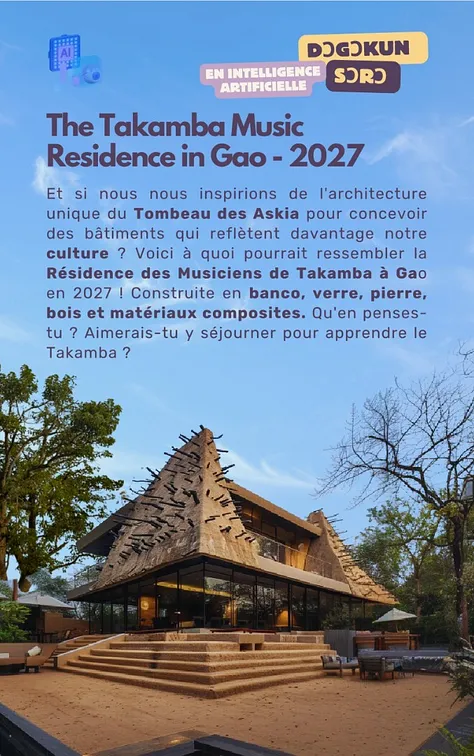

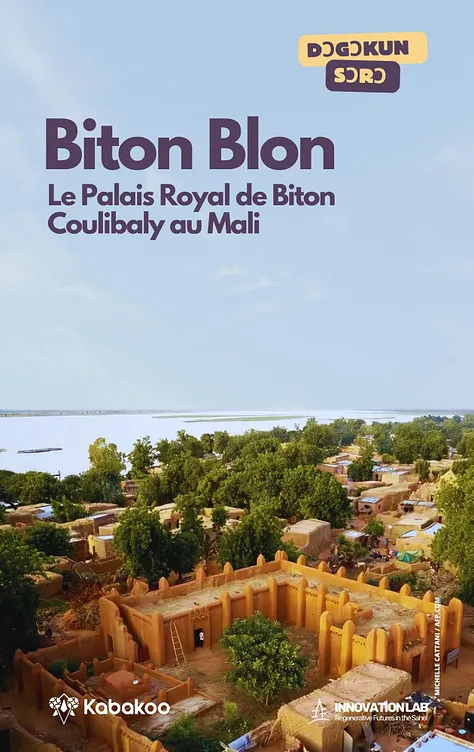

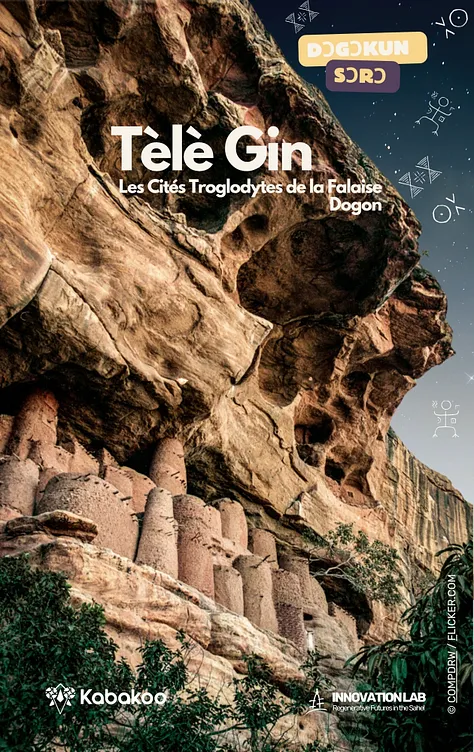

3. Dôgôkun Sôrô: From content to curriculum

Dôgôkun Sôrô (”treasure of the week” in Bambara) is our digital storytelling initiative dedicated to African architectural and material knowledge. Each edition starts from a place showcasing endogenous architecture—an earthen building, a granary, a royal compound—and tells its story: how materials were chosen, how forms responded to climate, how space organized social life.

Initially released as a written digital magazine, Dôgôkun Sôrô produced high-quality editorial content but saw limited engagement. When we shifted to video-based storytelling grounded in narration, engagement skyrocketed—the feature on the Royal Palaces of Abomey (Benin) attracted over 200,000 views on TikTok; the edition on the architecture of the Hombori Region (Mali) reached more than 622,000 views.

But the real value is of course not the views. These stories now serve as learning materials for our cohorts. When learners work on regenerative architecture projects, they directly start from these relatable frameworks. The storytelling effort hence produces reusable learning assets that scaffold technical skill development.

Why this matters for capability development

Recent research provides striking support for narrative-based approaches. In their review, Walsh et al. (2023) argue that stories play a role in the creation and maintenance of social bonds, shared understanding of collective issues, and cooperation toward common goals. Narrative interventions, i.e. helping people construct and tell their own stories, can hence produce measurable changes in self-perception, motivation, and goal pursuit.

Our own data aligns with this. In analysis of 504 learner portfolio entries, we found that learners who engage with storytelling tasks show systematic differences in how they talk about their futures, their capabilities, and their relationship to cultural knowledge. The “storytelling cluster” in our discourse analysis shows simultaneous high presence of cultural vocabulary (100%), creativity vocabulary (64%), and future-oriented language—precisely the synthesis that characterizes the Highdigenous approach.

Storytelling creates continuity between what learners already know and what they are discovering. Rather than ignoring or even asking them to abandon their references in order to access ‘new’ knowledge, it allows those references to become resources, i.e. points of entry for reflection, design, and innovation.

This is why we invest in storytelling infrastructure: not as media work, but as core learning architecture. The artisan portraits, the Dôgôkun Sôrô series, the learner testimonials are not marketing materials. They are a curriculum of culturally powered agency.

We have written a working paper formalizing this approach: “Highdigenous Pedagogy: Aesthetic Engagement as Epistemological Bridge in African Learning Communities”, currently under review at the International Journal of Educational Development.

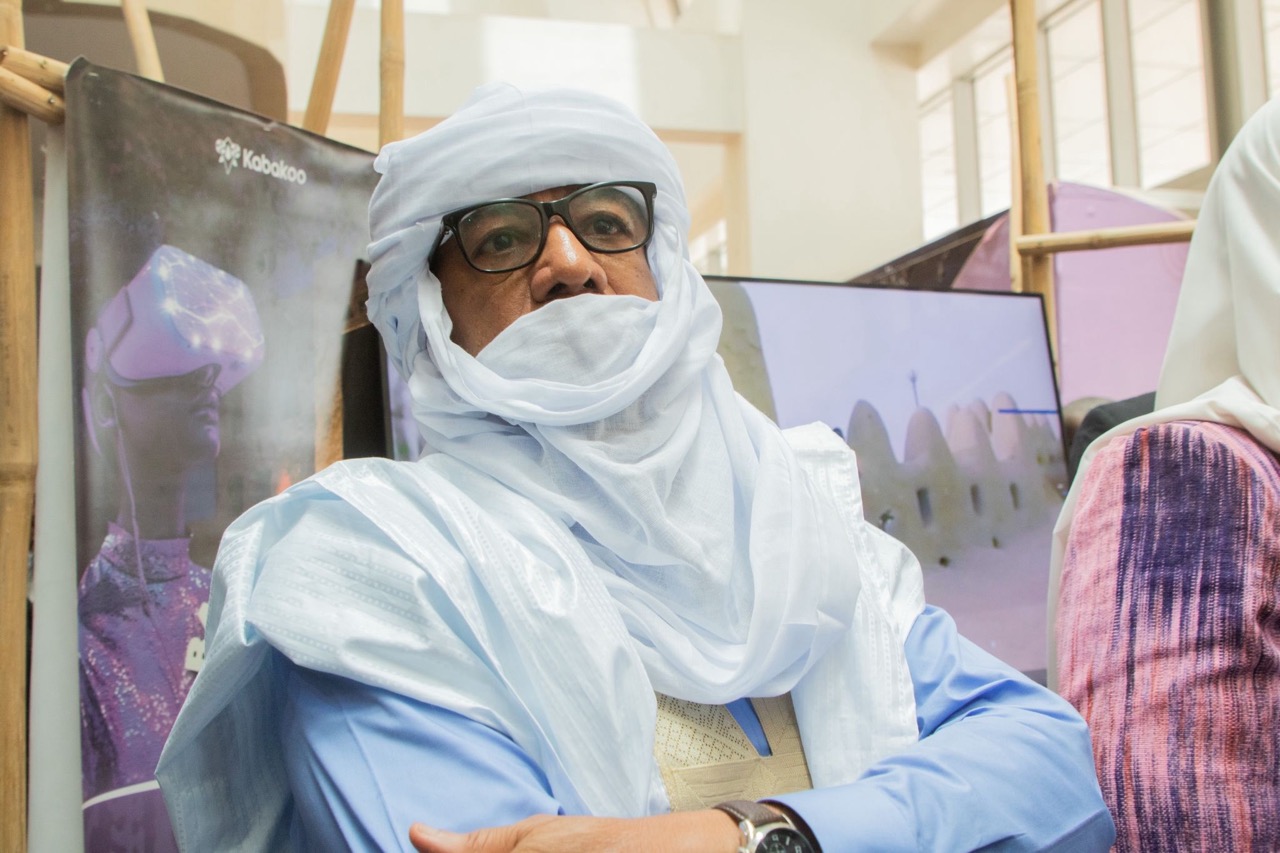

Kabakoo Faces

(With over 35,125 registered learners, each month we spotlight a member of our vibrant community.)

Amadou grew up in Birga-Dogon, a village in central Mali near the border with Burkina Faso. While many of his peers were pushed toward artisanal gold mining as a source of quick income, he made a different choice: moving to Bamako to pursue his education. At the time, his path seemed clear: get his degree, secure stable work, and support his family.

Enrolled in a master’s program in heritage at the University of Bamako, Amadou was soon confronted with reality. Despite studying hard and working multiple jobs, he struggled to see a clear future. Caught between university and the grins, the pressure to provide for his family grew heavier, often keeping him awake at night.

“People around me saw me as someone who was worth nothing, someone who spent all his time making tea with no clear goal.”

Everything shifted when Amadou discovered Kabakoo and joined the Regenerative Architecture program. The turning point came with the core modules on mindset and visualization. This new momentum allowed Amadou to deepen his expertise in heritage and architecture, strengthen his English, and learn to work with AI tools. His most visible transformation, however, was in public speaking. Once afraid to speak in front of others, he now facilitates workshops and mentors learners, earning the nickname “professeur”.

This is also reflected in his increased self-confidence. Today, for instance, Amadou wears his Dogon cap with confidence, something he once avoided out of fear of judgment.

“I used to be ashamed of wearing our local attires, but my perception changed with Kabakoo. Today, I wear them with pride.”

Amadou’s journey exemplifies what the Kabakoo Learning Experience aims to build: not just skills, but the ability to project and act forward, socially, professionally, and psychologically. Watch his full story here.

Thank you for reading to the end! 💜🧡

Michèle & Yanick